The Nick Gulas Sports Arena at the Fairgrounds Nashville

A mid the cacophony of construction going on at The Fairgrounds Nashville, it can be hard to hear.

New buildings are going up, replacing the aging structures that will be pushed over to make way for a glitzy new Major League Soccer stadium, which will become the century-old site’s centerpiece when Nashville’s new team takes the pitch there in 2022. Memories and history are trapped in the old Bricko blocks, but memories are fading, and the history is falling away and crumbling like the paint on those old walls.

The fairgrounds have been the site of much political sturm und drang over the past decade or so. Mayors and progressively minded types have foamed at the mouth over the prospect of developing the acreage into Something New. Pioneers (or gentrifiers, depending on one’s perspective) have clamored about the noise from the old speedway that still runs races on the site. Fewer and fewer people have attended the state fair that gave the land its name and its purpose.

But for years, there were different people foaming at the mouth, a different kind of sturm und drang.

In one small building, at the edge of the row that greets visitors when they climb the startlingly steep hill at the center of the fairgrounds, on Wednesday nights for years and years, thousands upon thousands would cram onto rickety bleachers or try to scoot their way into comfort on floor-level steel chairs — all of them keen to watch “the greatest wrestling in the history of the world.” Listen hard and you’ll hear the echoes of their cheering, but you better do it soon.

The sports arena at the fairgrounds bears the name of the man who coined the grandiloquent phrase that for years drew wrestling fans to the live shows (“tickets available at the box office or in the lobby of the Sam Davis Hotel”). Nick Gulas was born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1914 and worked with a wrestling promoter there. In 1940, he moved to Nashville, teaming up with Oklahoma native Roy Welch to stage shows. Welch was a true pioneer in wrestling — in fact, he might well have been one of the inventors of the predetermined style, depending on which researcher one believes.

As wrestler CM Punk famously claimed, professional wrestling is one of the few purely American art forms, along with jazz and comic books (though the case for the other two of the trio is much more tenuous). Pro wrestling had been part of the Nashville cultural landscape since long before Gulas and Welch put on that first show, which netted the pair $88, outside of the old Hippodrome on West End. The earliest indication of big-time wrestling in the city came on April 26, 1907, when world welterweight champion Al Akeman battled Canadian champ Fred Bartel on the venerable stage of the Ryman Auditorium. Giuseppe Creatore, one of the most famous bandleaders in the world at the time, and his band performed between rounds.

Thus, wrestling has a far longer history here than even the city’s best-known cultural contribution: The Bristol Sessions wouldn’t “invent” country music until 1927; the Grand Ole Opry didn’t debut until 1925 and didn’t come to the Ryman until 1943; and Sheb Wooley didn’t record “Oklahoma Honky Tonk Girl” until 1945. Though legend has it that Queen Victoria mused that the Fisk Jubilee Singers came from a “music city” in 1873, it wasn’t until 1950, when WSM’s David Cobb used the phrase during a broadcast, that Nashville’s nickname entered the broader zeitgeist.

By that time, Gulas’ shows were already filling the cavernous Hippodrome every week, with fans pouring into the roller rink/gymnasium/all-purpose building to see the sport’s first big stars. At the time, those stars included Herb Welch, Roy’s brother, already an established draw throughout the South, a man who, in more than three decades working Nashville (much of it in the pre-television days), main-evented more than 200 sellouts.

As a wrestler, Herb was a classic good guy — a “babyface” in the parlance — but it was a vicious heel that launched Gulas and Roy Welch into the big-time. Most promotions relied on their babyfaces to sell tickets, but for years in Nashville, the despised bad guys were the stars who brought people into the door — and many times nearly brought the house down, literally.

Pat Malone, who wrestled as The Green Shadow, came to Nashville with Roy Welch — both men were known for training wrestling bears — and became the villainous foil to the beloved Herb Welch and other fan favorites.

The Shadow generated so much heat with the live crowds that riots and in-stand fights were de rigueur — to the point that Nashville police officers who worked security at the events demanded a raise from the promoters. In one famous incident, a fan jumped into the ring after a Shadow victory and pulled a knife. The Shadow, unimpressed, pulled his blade and chased the interloper out of the building. Once police and the Shadow’s fellow wrestlers arrived, the wrestler had the fan pinned to the ground, knife at his throat, and was making to decapitate him.

In 1948, local wrestling promoters across the country formed the National Wrestling Alliance, an organization that dominated professional wrestling until the rise of Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Federation in the 1980s. In essence, the NWA was a cartel. If rival promoters tried to put on shows in a member’s territory, other NWA members would send their top draws to town to choke out the competition. Gulas and Roy Welch were among the charter members, but unusually, for their entire run, the Nashville territory almost always relied on homegrown talent for its success. The territory later included Memphis, Birmingham — which Gulas integrated on a whim in 1963, booking a main event that featured Hawaiian Japanese wrestler Tojo Yamamoto and African American wrestler Bearcat Brown — Chattanooga and Knoxville, plus scores of jerkwater stops in the area. (After the ’63 match, Bull Connor, Birmingham’s public safety officer and a passionate segregationist, barred wrestling in the Magic City until the passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year.)

The formula of using local talent worked well because Nashville focused on lengthy feuds — decades-long in some cases — that kept fans coming back for more. Unfortunately, it also means that Nashville wrestlers’ place in the broader history of the glory days of professional wrestling is barely a footnote. Over the course of 40 years, every NWA champion but three defended his title in Nashville, but only one Nashville-based wrestler — Hendersonville’s Tommy Rich — ever won the alliance’s Big Gold Belt in the same period.

By the mid-1950s, the two-hour Saturday night wrestling broadcast on WSIX-TV (now WKRN) was a staple and a ratings monster, fueled in part by the success of the Fabulous Fargos. The Fargos were a brother tag-team that included Jackie, who invented the famous “strut” many people mistakenly believe was created by Ric Flair.

In a 1975 interview with The Tennessean’s magazine, Gulas bragged that in one city his broadcasts had double the ratings of Southeastern Conference basketball, six times that of the Big Ten and 66 percent of the NBA — and those figures were for hoops-mad Evansville, Ind. Broadcast all over the South and into the Midwest, the show was a hit, regularly drawing 600,000 viewers in the Memphis broadcast catchment at a time when the city of Memphis itself had a population of only 650,000.

Nashville’s aging Hippodrome shuttered in 1968, and Gulas and Welch needed a new home. They relocated their Wednesday night shows (and the occasional Friday night and Sunday matinee shows, to boot) to the old Coliseum at the Fairgrounds, which had been built by itinerant workers from South Dakota in 1922. Thus began the long symbiosis between the fairgrounds and pro wrestling, a relationship that will end Saturday, June 1, with the Farewell to the Fairgrounds card, a joint venture between local promoters Overdrive Pro and Tommy Dreamer’s House of Hardcore.

The Coliseum was the source of much worry by the time Gulas started jamming 5,000-plus people into it every week. The night before the 1965 Tennessee State Fair opened, a fire tore through the fairgrounds, destroying or damaging many of the Coliseum’s contemporary buildings. Miraculously, the fair opened on time, an anachronistic testimony to how much people cared about the fair in its halcyon days. Metro ordered a review of the safety of the fairgrounds’ oldest structures, including the Coliseum, and the final report deemed it “a dangerous fire trap.”

“A fire, starting either in the bleacher area or the storage rooms, would be transmitted in minutes to the roof,” the report stated. “With crowded exits, possibly blocked by flames, it is difficult to predict anything other than a major disaster, were the Coliseum occupied.”

Nonetheless, the shows went on undeterred, the old building groaning to capacity week after week. Gulas later boasted that sometimes he’d have to turn away as many people as he let in, because demand was so high. By the turn of the decade, the Nashville-based territory was running shows in 48 cities — more than any other member of the NWA.

But on the night of Feb. 10, 1970, the predictions came true. Flames shot 100 feet in the air, and the old Coliseum was destroyed in less than an hour. It took 45 firefighters to tamp down the blaze as Mayor Beverly Briley and scores of other Nashvillians, drawn to their beloved building by the sight of flames visible throughout the city, looked on. (Mercifully, nobody died in the conflagration, though two firefighters suffered minor injuries.)

On the scene, Briley promised that a new venue would be built — eventually — but that the insurance on the Coliseum wouldn’t cover construction.

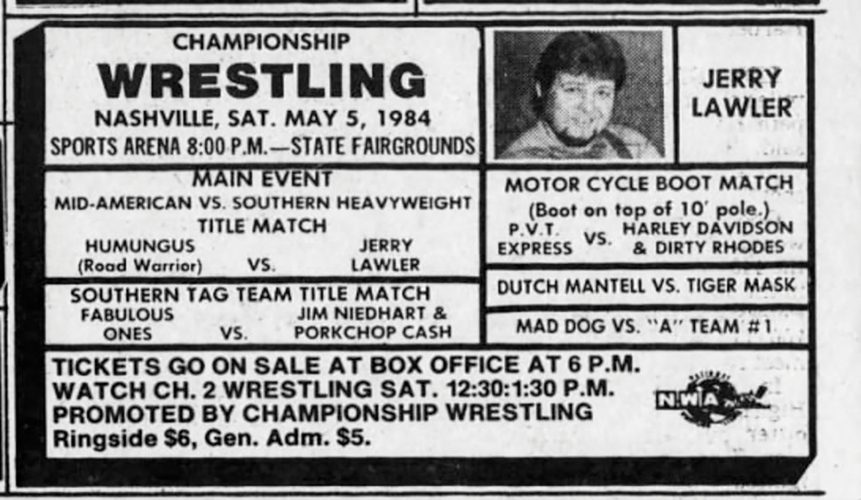

Ad that ran on May 5, 1984

Despite the massive setback posed by the fire, live wrestling in Nashville was interrupted for only a few weeks. Gulas and Welch considered building their own arena while Metro and the fair board licked their wounds from a second major blaze in five years. In the meantime, the promotion found other places to put on its shows, including the Father Ryan High School gymnasium. They ultimately settled back at the fairgrounds, where for years they rotated between various buildings — the exhibition hall, the women’s building, the agriculture barn. No matter what, though, the cards were advertised, rather confusingly, as being held at the Fairgrounds Arena. Perhaps, just as any airplane carrying the president is Air Force One, any arena hosting the Fargoes and their opponents du jour (including, for the first time, a touring André the Giant) became the Fairgrounds Arena.

Despite the itinerant setup, business thrived. Presumably, the crowds who made their way to the fairgrounds were directed to whichever building was the “Fairgrounds Arena” that week. Gulas had taken on a new assistant, a diminutive single mother named Christine Jarrett, who everyone called “Teeny” as long as she wasn’t mad at them at the moment, in which case she’d be “Mizz Jarrett.” With his empire at its apex and his old partner Welch aging, ill and spending more time at his farm in Dyersburg, Gulas needed a hand. His power and influence were strong, but even the man called the King of Wrestling couldn’t be in two places at once.

Wrestling’s history with women is, to put it mildly, a complicated one. For every inspiring tale about Mae Young busting the glass ceiling imposed by men and getting women wrestlers the pay they deserved, there’s another story like that of woman wrestler The Fabulous Moolah — Young’s best friend — who by many accounts held other women back, withholding their wages and even literally pimping them out to promoters.

But there are unmitigated success stories of women who became formiddable promoters in their own right. Lia Maivia — you may have heard of her grandson, Dwayne Johnson — is often credited as the first woman promoter, as she ran Polynesian Pro Wrestling after her husband died in 1982. While Teeny Jarrett didn’t hold the formal title, she was a promoter in all but name, running some of the towns in the territory while Gulas handled the rest.

And her natural knack for the business became a family trait. Her son Jerry — who had tagged along with his mom for years, taking tickets at the Hippodrome and getting a hardship driver’s license to help promote shows when he was 14 — started wrestling in 1965, winning a Southern tag title with Yamamoto and finally debuting in his hometown in 1971.

With Welch laid-up (he would die in 1977), Gulas leaned even more on the Jarretts mère et fils and longtime employee Eddie Marlin, already legendary as a referee and later a promoter in his own right. This was particularly true as Gulas groomed his son George for an in-ring career.

Though the fair board and Metro had made repeated promises to build a new sports facility at the fairgrounds, progress was slow through much of the 1970s. The fair board was tasked with the project of revitalizing what is now Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park, where a football stadium to be shared between Vanderbilt and Tennessee State was then planned, along with a new minor-league baseball park. Nevertheless, despite the lack of a purpose-built home, Nashville wrestling thrived, making new stars in the Valiant Brothers, Jerry Lawler, Superstar Bill Dundee and others who, because of the money to be made and the crowds drawn in the Bluff City (not to mention the better venue at the Mid-South Coliseum), got pegged as Memphis wrestlers. That’s despite the promotion’s office being in the state capital.

But in 1978, the Metro Fair Board finalized its plans for the new sports arena, a 4,200-seat facility with high ceilings — a necessity noted by the board’s chairman, John U. Wilson, who pointed out that wrestlers were hitting their heads on the 12-foot ceilings of the Exhibition Building — at a cost of $450,000 in fair funds, with a substantial investment from Gulas as well. It swung open its doors in 1979 with a card headlined by Lawler, who defended his Continental Wrestling Association title against Superstar Billy Graham, a sort of ur-Hulk Hogan.

The CWA was a creation of Jerry Jarrett, who had purchased a percentage — he thought he was buying 10 percent, but in fact, Gulas had given him a lot less — of the Memphis/Nashville territory in the mid-1970s. By this time, many of Gulas’ wrestlers were getting upset because George Gulas, who was not a particularly talented or athletic wrestler, was getting booked to win matches, especially in the Memphis half of the territory. In an infamous 1979 match, Nick Gulas booked the tenderfooted George to take on visiting NWA World Champion Harley Race at the fairgrounds’ Sports Arena, a spot he was in no way prepared for. Partially to show solidarity with the upset local roster and partially to show his personal distaste for having to wrestle Gulas to a draw, Race refused to “sell” Gulas’ objectively awful punches and chops, prompting George Gulas to famously shout at the iconic Race, “Daddy says sell!”

The talent revolt, coupled with what Jarrett perceived as a double-cross by Gulas, led to the pair splitting in the late ’70s, with Jarrett running Memphis — at that point more successful than ever because of Lawler — and Gulas running Nashville. At its best, it was a fractious arrangement, though there were clearly still some talent exchanges, as Lawler and Graham were both working for Jarrett when they helped open Gulas’ new building.

As more and more of his big names defected to Memphis, Gulas eventually ceded his territory back to Jarrett in 1980. Jarrett ran the fairgrounds arena, managing the statewide wrestling empire from his impressive hilltop mansion in Hendersonville, where he lived with his wife Deborah — Eddie Marlin’s daughter — and his son Jeff. While Gulas remained with NWA until the end, Jerry Jarrett left the old alliance for a competitor, the American Wrestling Association, in 1978.

In the 1980s, the NWA still came to town, but it staged shows with big stars like Ric Flair and Ricky Steamboat at Municipal Auditorium, while the Lawler-fueled CWA kept up appearances at the fairgrounds’ Sports Arena. Jarrett made the big money in Memphis, and the Sports Arena — Gulas’ name was officially appended to it when he died in 1991 — was just an occasional stop on the CWA’s loop.

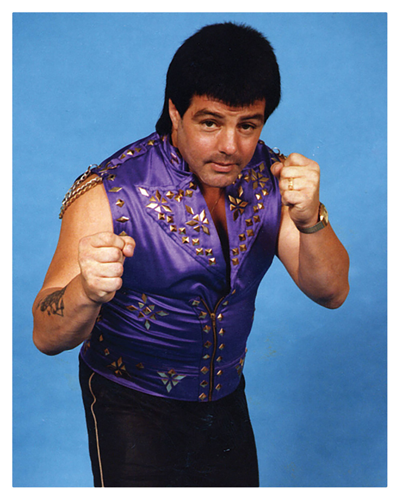

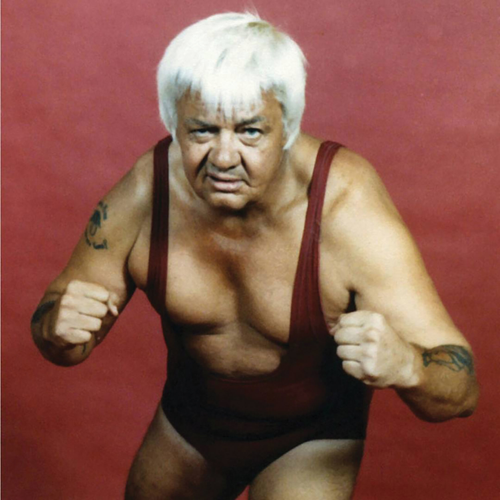

Bill Dundee

Wrestling changed in the mid-1980s, when McMahon took his promotion national, and the NWA birthed World Championship Wrestling, eschewing decades of the territory-based tradition. Eventually WCW split from the NWA altogether, surviving until it was swallowed by the WWE in 2001. The other competitors — the CWA and its successors and partners — didn’t last long beyond the early 1990s. A rump NWA kept going, but through the 1990s it was clearly America’s distant third choice, increasingly seen as stodgily old-fashioned: RC Cola in a market dominated by Coke and Pepsi. It was this level of wrestling that populated the Sports Arena, as the bigger promotions stuck to Municipal and, later, what is now Bridgestone Arena. Nevertheless, Jerry Jarrett kept his reputation as one of wrestling’s smartest figures. For example, in 1994, when it appeared certain Vince McMahon would go to federal prison after a steroid trial. A jury ultimately acquitted McMahon, but it’s rumored he’d tapped Jarrett to run the company were he to be incarcerated.

Jeff and Jerry Jarrett re-emerged in 2002, announcing a new promotion: Total Nonstop Action (yes, the initialism was a response to the extremely PG-13 Attitude Era of the WWE). TNA would affiliate with the NWA, and Jeff Jarrett would join Tommy Rich as the only other Nashville-area native to win the NWA title. There’s a strange irony in fact that the victor would be Jeff Jarrett, the son of the man who left his old partner in part because of nepotism, that old partner having made his bones years before on the back of his old partner’s brother.

In its early days, TNA — now called Impact Wrestling — followed an unusual model, avoiding broadcast and cable television altogether, instead putting its weekly one-hour shows on pay-per-view, partly as a way to show viewers that the product would be edgier than the WWE’s. The WWE had become a public company in 1999 and was recovering from the steroid trials and the debacle of the XFL, trying to rehabilitate itself with a more kid-friendly product. Until 2004, when the TNA went to a more traditional model and began producing its shows from a Florida soundstage, the fairgrounds Sports Arena hosted 111 TNA shows. The space was dubbed “The Asylum” by Ron “R-Truth” Killings during the ninth show at the building (Killings is, to date, the only African American NWA Heavyweight champion, a much prouder accomplishment for him, surely, than teaming with Pac-Man Jones to win the TNA tag team belts in 2007).

Jackie Fargo

And that name is the one most people still use when referring to the old building. When Jeff Jarrett brought the NWA back to town in October 2018 for that promotion’s 70th anniversary show — a sellout that set the box-office gross record for the arena with its main event between Nick Aldis and Cody Rhodes — the venue was branded under The Asylum name. The nickname is also occasionally referenced by what was the building’s primary tenant for the better part of the past 15 years — the women of Nashville Roller Derby.

It’s fitting that the fairgrounds arena is meeting its final fate, demolition, not long after the NWA show. But there’s always a peroration, always more stories to tell, in wrestling. So instead, the final farewell will come with local startup Overdrive PRO, which itself will be looking for a more permanent home. And the crowd will be hooting and hollering at the old Sports Arena, cheering on their favorites. And because this is still Nashville, one of those favorites will be a native with a lengthy history and feuds that stretch generations, as Antioch High School graduate Ricky Morton will team, as he always does, with Robert Gibson as the Rock ’n’ Roll Express. The former will no doubt find himself in trouble, as he he has thousands of times — so many times, in fact, that such a role in a tag match is actually called “playing Ricky Morton” — before the tag to Gibson, who will come in like a house afire.

The cheers will echo one last time, adding their strains to all the cheers still trapped in those old walls.

A previous version of this story inaccurately stated that Roy Welch died in 1999. He died in 1977.